Everything, not Every Thing

On Niche and Limitations

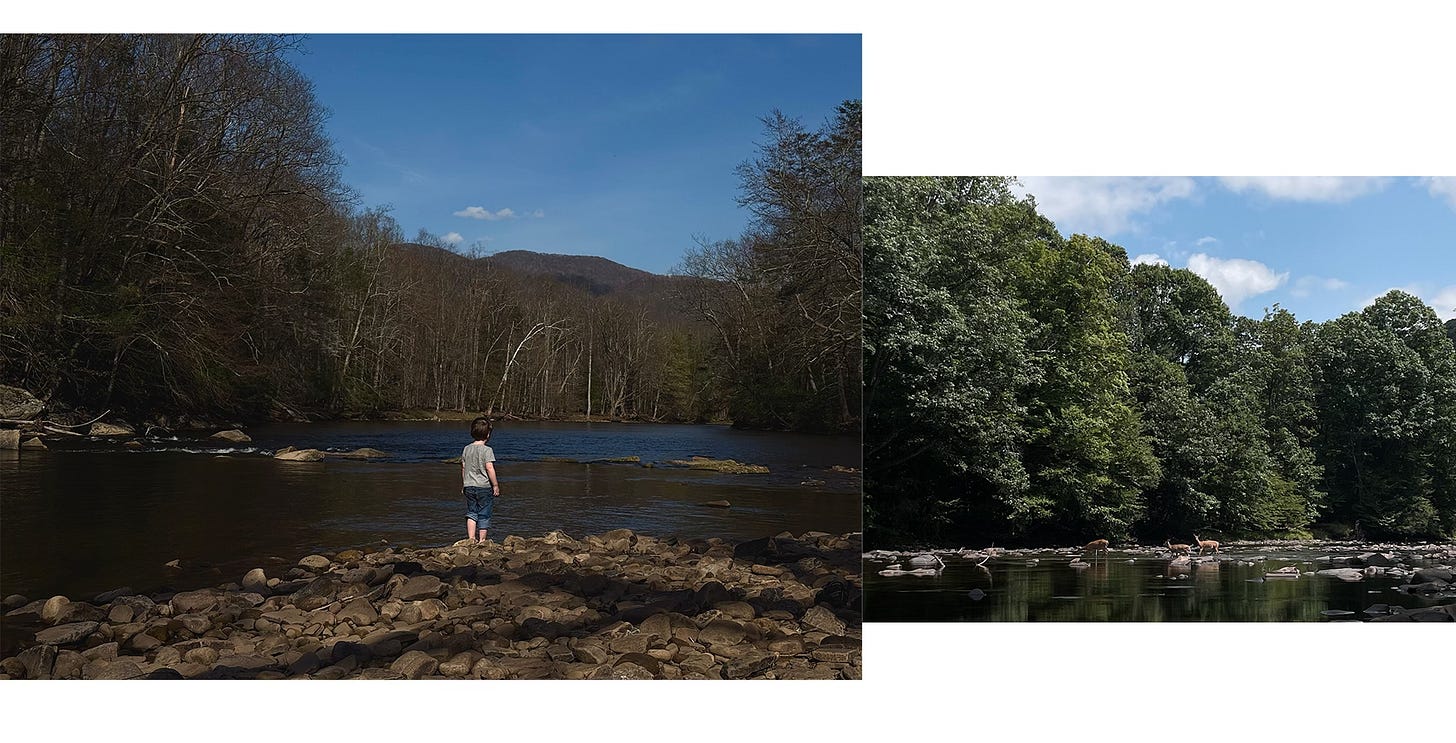

Yesterday, we took the kids to Shavers Fork. We took off our shoes, threw stones in the river, played in the cold water. Remy stood near the same place where I previously photographed a deer family crossing the water (see bottom of post for that cuteness).

That familiar bend in the river was a frame I’d once imagined. A while back, I remember Curren and I standing there also - without kids, saying out loud—this is the place to raise a child.

There was something comforting in the recognition—to want something for your life, and then see it. I felt lucky. It was in that moment I remembered that I wanted to raise my kids in this place not because it has every thing—it most certainly doesn’t. But because it has everything.

Everything isn’t just a word I’m interested in academically. It’s a question I return to over and over again.

I ask: What is my everything? And is it also my enough?

If you don’t know your everything—your enough—you may feel adrift from time to time. The world can feel both too noisy and too big, yet somehow too small to find a seat. Exploring your thinking around niche can help guide you.

I remember learning the distinction between every thing and everything from the wise Wilma Dykeman. She wrote about her experiences in Greece and compared them to the mountains where she was raised in Western North Carolina:

“More than sixty percent of Greece is mountainous. And along this winding road the loneliness and harshness which lie at the core of life is starkly revealed. In our inventive society of things, devices, objects, such knowledge is hard-won, or never won at all except through vague and disquieting second-hand hints which scarcely penetrate the daily noise and tight routine.

If I ask how the dweller in that crude shelter confronts the grip of winter, the imprisonment of storms, the seeming barrenness of his landscape, I hear echoes of acquaintances who ask how people live in the hills and valleys of the Appalachian ranges—‘so far from everything.’

What is ‘everything?’ Is it, in fact, every Thing?

If so, then mountains—in Greece, in Appalachia—can bear messages for survival. I remember a son and his wife telling me of meeting a Sherpa woman carrying her heavy burden along steep trails in Nepal, over the rocks, in high thin air, and singing.

Mountaineers in numerous civilizations have been called isolated. Isolated from what? From whom?”

Wilma recognized that geography is never just backdrop—it shapes how we cope, how we celebrate, how we find resilience.

So when she wrote, “People ask how others live in these hills, so far from everything,” I think what she was saying is: maybe everything doesn’t mean more. Maybe it means what matters.

I think this because it’s clear she knew what mattered to her; she had her niche. I know this because her life’s work was shaped by the French Broad River and the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. This niche she carved out — within the world of human geography and environmental writing—was where she expanded and contracted her thinking over the years through fiction and nonfiction.

In many ways, I think niche is undervalued today. In other ways, I think social media rewards niche, though in a different way. It buckets our identities and serves us more of the same. But your niche isn't a brand. It’s a way—of paying attention, of circling back, of staying rooted while wandering.

What is niche?

Niche, by definition, is about limits. It's a chosen and narrow tunnel. And yet, it can be a form of freedom too.

To claim a niche is to say, “this is the scale at which I can pay attention.”

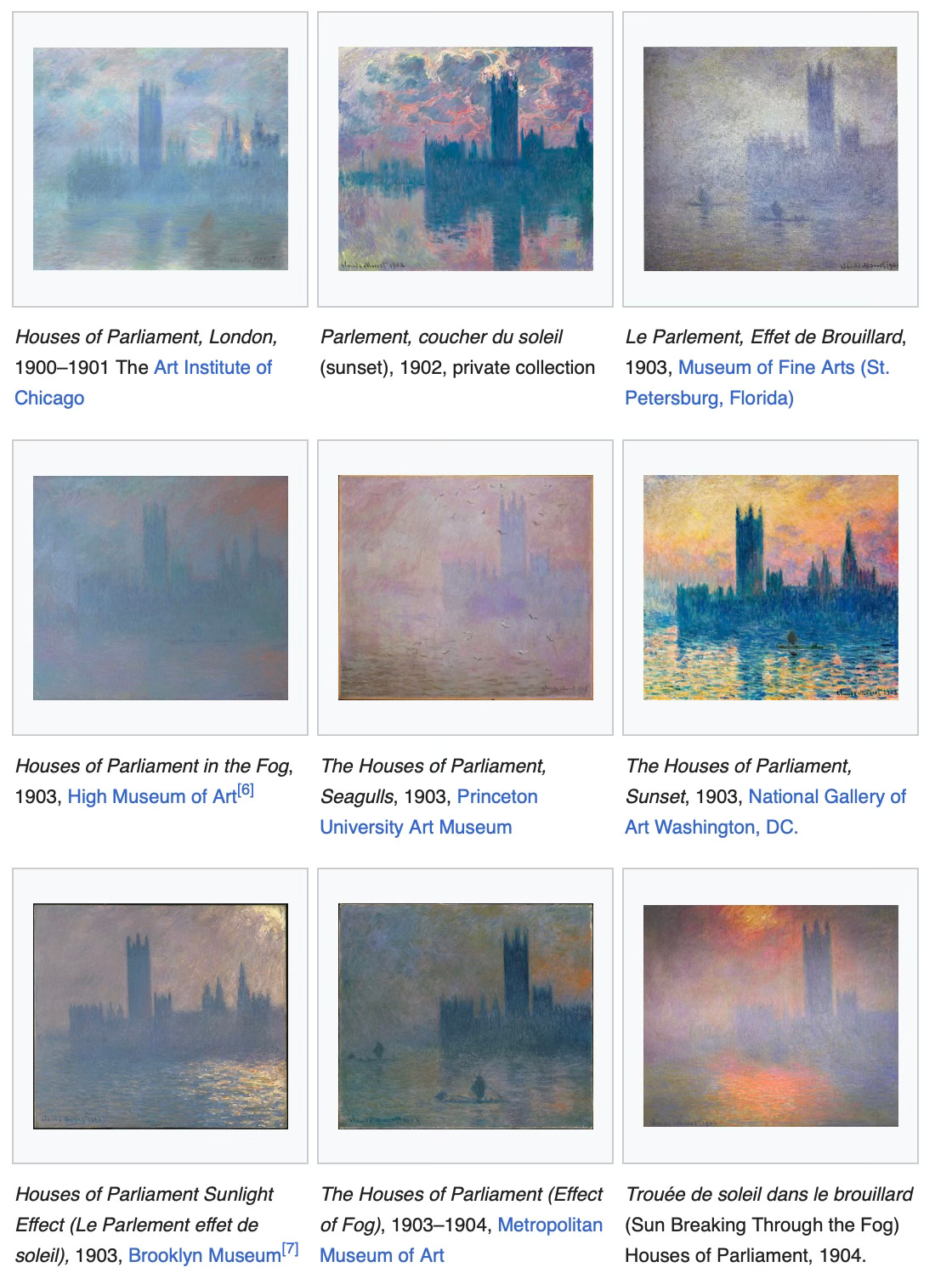

Painters have always known this. Think of the ones who painted the same mountains or light patterns over and over—not because they had nothing else to say, but because the repetition allowed them to say something new each time. Monet had his Houses of Parliament. El Greco had saints. Anni Albers had geometry and thread. The niche—along with the materials and the medium—didn’t confine them. It gave them a rhythm.

A niche can be your definition of everything, of this is enough for a project and for your life. Isn’t all great art - and conscious living - just the result of deep attention?

Every film project is its own niche.

You have to obsess over a topic and then move to the next. That’s actually what I love about filmmaking. When I start a project, I’m usually starting from a point of not knowing. I know the skills I need to get to the answers, but I don’t know them yet. The average documentary filmmaking career could throw you into various topics you become a temporary expert on: Vaping. Farming. Girls’ basketball. Deep sea fishing. Wildfires. Kindergarten education. Autoimmune diseases.

These are the topics—the niches you are exploring—but your job is to find the story. The niche provides the funnel. You read, watch, listen to all things that fit in the funnel, and the shape on the bottom is the film you make. We could all choose the same topic—freshwater lakes—and come out with very different projects.

That’s what makes filmmaking alchemical. It’s not just about facts. It’s about point of view. And I think that’s true of all great art.

Your point of view is not neutral.

Your point of view shaped by place, upbringing, faith, love, failure, sleep, grief, food, weather, music, and myth. In other words, your niche isn't a brand—as people trying to sell you into selling things to others will tell you. It’s a way—of paying attention, of circling back after wandering.

So - is there a world where your niche opens up a greater path away from the heavily populated stream of people and noisy crowd?

Can niche give you clarity when you don’t know what direction to turn?

Or is it too limiting? It’s up for debate.

Recycling stories

The other day, when I was cooking, I looked out the window at the vultures swirling in the sky. Even vultures—those solitary creatures we see circling in wide skies—move in community. They have their own social order. And I’ll bet not one of them wakes up thinking, I don’t want to be a vulture today, but I don’t know what else to be.

Yet, many, many of my conversations with creatives as of late have taken that tone. My fellow artists—smart, curious, committed people—carry this undercurrent of drift. We’re questioning our direction, our usefulness. Maybe it’s AI, maybe not. It’s as if the old stories we were told about success, productivity, visibility no longer match the shape of our lives.

And that’s not a failure. That’s a signal.

It’s a signal of loneliness, of displacement, of not knowing where to direct your energy. Of feeling lost inside stories that we have outgrown.

We don’t just inherit genes, we inherit narratives—about what’s possible. But if those stories don’t reflect who we are anymore, they can make us sick. Because disconnection—between body and place, self and community, past and present—breaks us.

So we need to tell new stories. But not throw away the old ones.

Because not all that we abandoned was useless. And not all that we build is worth keeping.

I’ll end where I began—by the water, throwing rocks with my kids. I wanted to raise them here not because this place has every thing. It doesn’t. But it has the everything that matters to me. Stillness. Space. Time. Curiosity. Kinship. And maybe these mountains are my niche.

But niche isn't a brand. It’s a perspective. A way of noticing. It can be as expansive or as small as you’d like it. But it’s where the story always starts again.

Obsessed with this. I am always thinking about the small view.

25 years or so ago I filmed with a woman in Tokyo, Japan who had photographed the clouds from the same window in her Shinagawa apartment every day for 30 years. She told me that the sky is always changing and her aim was to capture the moment. She mounted her photographs into albums and stacked up they were the height of a child. She was a true artist

Inspiring. Thank you, Elaine!