Mapping the Unknown

The Emotional Cartography of Creative Nonfiction

It usually goes like this.

A thought at 2am gets me out of bed.

I draw what I see. I write what I hear.

Sometimes it makes sense in the morning.

Other times, it doesn’t.

But either way, something shifts.

A new connection gets made in the dark.

This is how films unfold for me—not with a perfect outline or tidy idea, but with fragments. Flickers and shapes that don’t yet have names. I log the unfamiliar and awkward shapes so as not to forget them. I feed them to the project, and somehow it grows. I used to think I was building the film, but lately, I think the film is building me.

Making a documentary feels like constructing a brain—alive and always processing—or maybe like charting a nervous system. A system that fires in directions I can’t always predict. Ideas lead to phone calls, phone calls lead to shoots, shoots to discoveries, discoveries to new questions. It’s a brain, a growing machine, that builds momentum not from control, but from curiosity.

Every day, I feed this brain—research, conversations, footage, photos, memories, half-thoughts on sticky notes. And in return, it teaches me things I didn’t set out to learn. A door opens. Another closes. And I follow. That’s the only way I know how to do this work: by staying close to the signals. The film and I are learning each other’s rhythms. It’s alive in that way—more like a relationship than a product.

Or maybe not a brain, nor a machine, maybe it’s an atlas.

Kate Crawford, in Atlas of AI, offers a metaphor that helps me make sense of this: “AI,” she writes, “is like an atlas.” But she’s not talking about a tidy road map—she’s talking about a way of seeing. “When you open an atlas,” she says, “you may be seeking specific information about a particular place—or perhaps you are wandering, following your curiosity, and finding unexpected pathways and new perspectives.”

That feels true to my process of filmmaking, too.

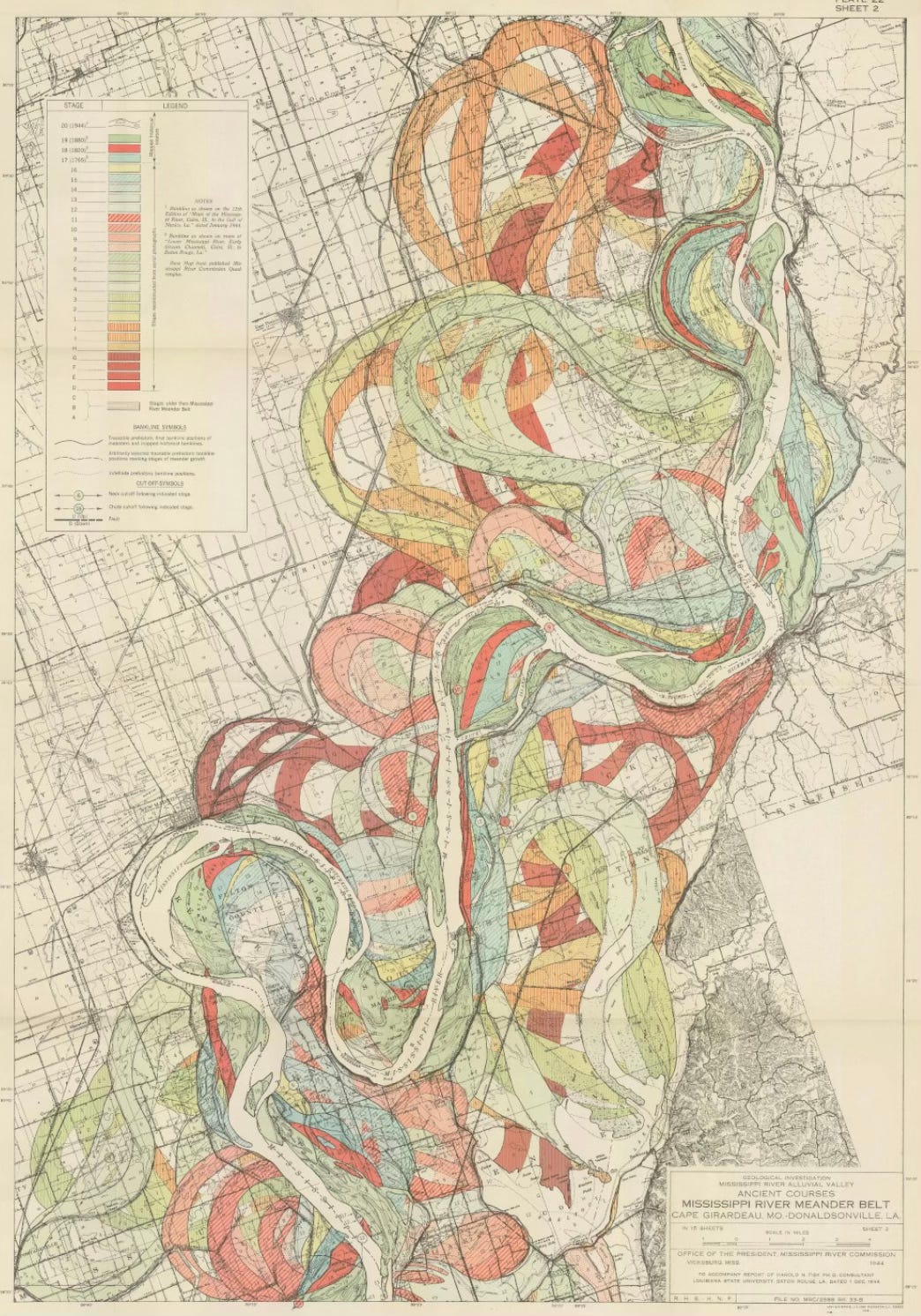

An atlas, Crawford reminds us, isn’t neutral. It’s both science and creativity—an aesthetic and political act (see image above). A way of declaring what matters enough to be mapped. It gathers details and attempts to locate truth in the vast. But it also invites wandering.

At their best, maps are a “compendium of open pathways”—a collection of ways to reread the world, she writes.

In the case of a documentary, a map forms, but it’s never finished. New terrain keeps unfolding. New roadblocks emerge. One conversation leads me to a place I couldn’t have anticipated. A “no” forces a redirection. A gut feeling (something that’s hard to name) points to the next stop.

You can put a date on the calendar, say, “This is when the map will be done.” But finishing doesn’t always feel like arriving.

You don’t always know what the thread is until the very end—or maybe not even then. Maybe you only figure it out when you’re talking on stage during a Q&A, after the film is finished. You have an aha moment… you realize what it was you were seeking. And in your darker moments, you now see what you missed.

That’s what I’m after:

Not a summary.

Not an argument.

But a map that invites new interconnections—and draws the senses into the experience.

A way through the thicket of information, emotion, memory, and place.

A way of learning that’s always alive.

So when I say I’m working on a film, what I really mean is: I’m following it.

And if you’re in it right now—in the weeds of your project, not sure what to trust—know that it’s okay to not know. Just keep feeding the brain. Keep listening.

The map will make itself.