On Independence and Asking for Help

the value of surrendering

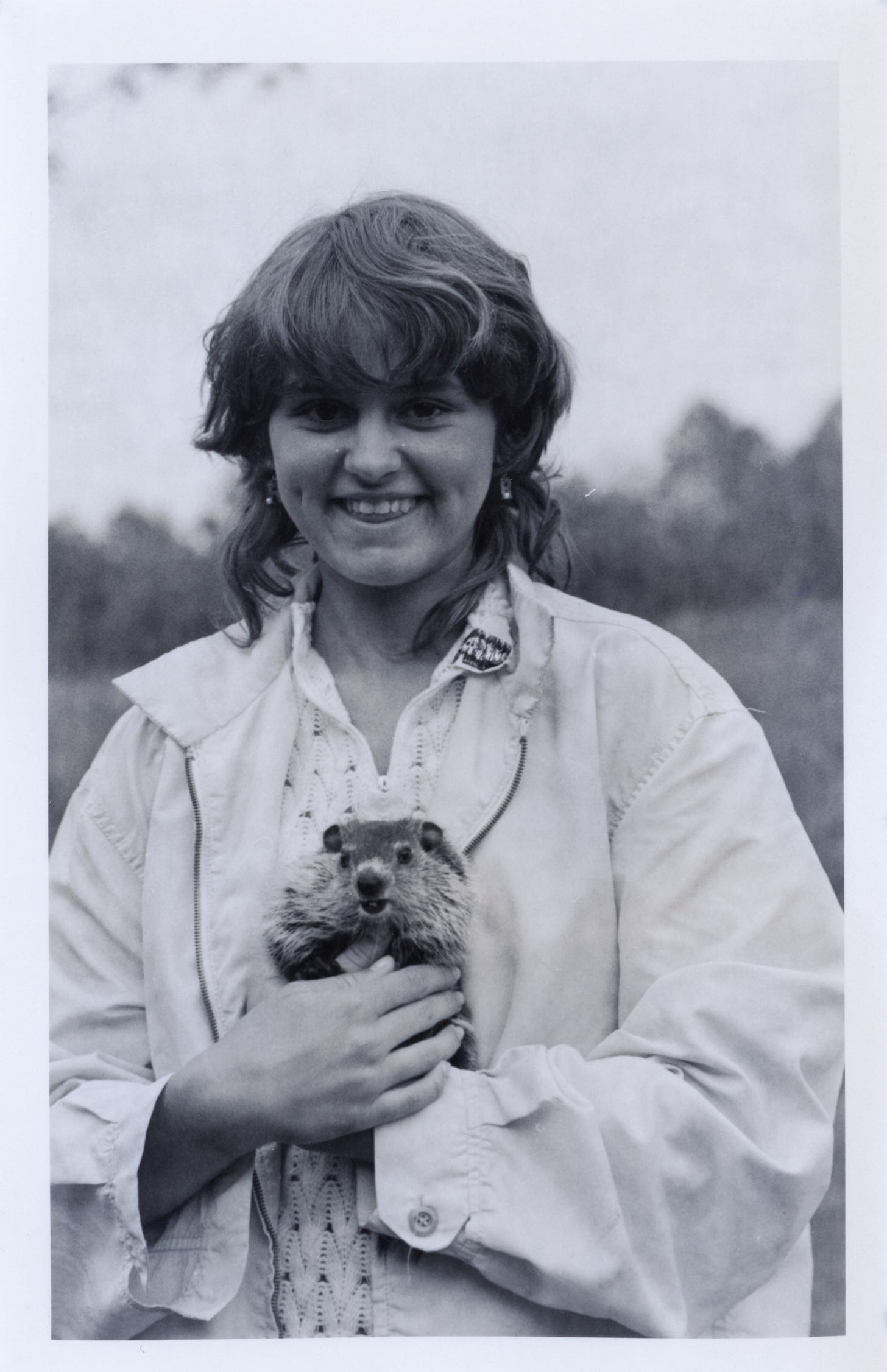

Today is my mom’s birthday.

It’s snowy outside—a foot deep, with sharp icicles hanging from the windows. The sidewalks are slick, frozen solid. I send my mom pictures of the snow, these moments I see as quiet and beautiful.

Her response? “Yuck.”

She hates the snow. And I get it.

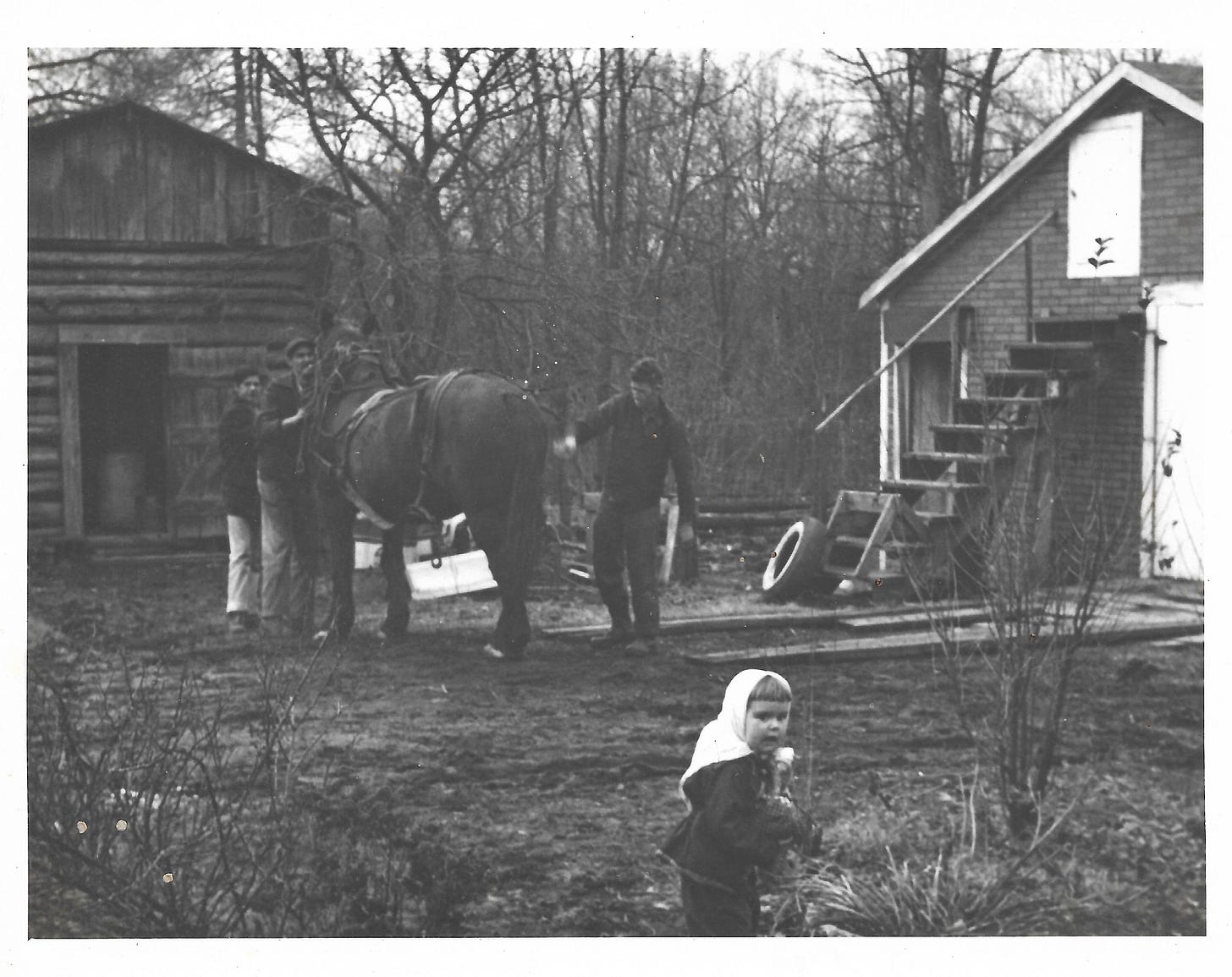

She grew up on a farm in Nicholas County, West Virginia, where snow wasn’t pretty or romantic. It was a barrier. It meant cold mornings gathering eggs, trudging to the barn to milk cows. It meant deep drifts so heavy you needed a snowmobile just to get out. Snow was work. Snow was survival.

My great-grandmother lived that life too. She milked her cows until she physically couldn’t anymore. She was the kind of woman everyone called on—taking care of family, neighbors, anyone who needed her. I was only three when she died, so I don’t have clear memories of her, but her reputation looms large. I don’t know if she liked the snow, but I doubt she gave it much thought. When you’re that tied to the land, you don’t get to choose what the weather brings. You endure it.

That endurance runs deep in the women of my family. Strong-willed. Determined. Opinionated. And, yes, stubborn.

Some are softer than others. My mom is on the soft side. She’s not the type to push her way through life, knocking over whatever stands in her way. Her strength is quiet.

She’s the kind of person who will make meals for neighbors without being asked, who will drive someone to a doctor’s appointment because they’re too old to drive themselves. But even though she’s quick to help others, she rarely—if ever—asks for help herself.

And, unfortunately, I’m the same way.

There’s this moment I keep replaying. When we recently moved a friend said to us, “I know you’re not the kind of people to ask for help, but if you need anything, just say the word.”

I laughed it off at the time, but it stayed with me—and, if I’m being honest, it kind of embarrassed me that it was so obvious. Curren and I are both wired the same way. We’ll grit our teeth and carry on, even if we’re overwhelmed, even if it means shouldering too much.

I think about this trait often, and I’ve come to believe it’s not just a family thing—it’s cultural. I was born in one place, to one kind of people, and those people are Appalachian. Appalachia is too complex, to be reduced to clichés. But I can’t deny there’s some truth to the idea of Appalachian independence—that deep, almost unshakable instinct to handle things on your own, to tough it out, to rely on no one but yourself. It’s part of who some of us are, for better or worse.

The Foxfire books capture this. If you’ve never read them, they’re a collection of stories, traditions, and how-tos from Appalachian life, started in the 1960s by a group of students and teachers in Georgia. They cover everything from building log cabins to natural remedies to cooking on a wood stove.

One story from Foxfire Volume 11 sticks with me. It’s a farmer talking about his half-sister, who raised him after his own mother died. He recalls how she worked from before dawn to after dark: cooking, milking cows, washing dishes, and doing just about everything else on the farm.

I bet there's not three women that done the work that she done. She’d go all day long. I'd ask her that night if she was tired, and she'd say, "Nay, I ain't tired." Why, I knowed she was give out. She didn't make us help her like she ought to either. She'd do it herself.

I recognize myself in that. I don’t milk cows every morning, but I carry that same reluctance to ask for help.

Asking for help is a kind of surrender.

It means letting go of control, handing over a task or a responsibility, and trusting someone else to step in. The hard truth is, when someone helps you, it won’t always be done the way you would have done it. It might look different. It might feel different. It might even taste different, if we’re talking about something like a home-cooked meal. But that difference, isn’t a burden. It’s not something to be resisted. In fact, it’s what makes asking for help so beautiful.

I’m writing this as much to convince myself as to share it with you. Because I am trying to remember that asking for help isn’t a weakness—it forges connection. It’s about letting someone else show up for you, in their way, with their skills and their rhythm. It’s hard, I won’t lie. But I aim to start seeing asking for help as an act of connection.

The way someone performs an action tells you a lot about who they are. Maybe they move slower than you do. Maybe they take more time or approach things differently. It just shows you how they process, how they think, how they approach the world. And in that difference, there’s a lesson.

We live in a world (especially artists) that often teaches us to believe that our own unique way—of thinking, working, acting, and showing up—is the right way, or even the only way. Someone else’s way of helping may not match yours, but it’s still valuable. And, in some cases, it might even teach you something you didn’t know about yourself.

In recent years, surrender has quietly become one of the most important parts of my creative process.

When you hand over your footage to an editor who approaches the material differently than you would, or entrust your work to a sound designer who layers their own artistry into it, you’re letting go of control—but in the most rewarding way. There’s something magical about communicating your vision and then seeing another artist interpret it through their lens.

I think about Shodekeh’s breath art in King Coal—how his body became an instrument, echoing the mountains in ways I never imagined. Or the community members who stood up to speak in the final scene of the King Coal memorial. It was collaboration in its purest form—unexpected, raw, alive.

This kind of surrender isn’t something I was taught to value in the beginning of my journey as a filmmaker. In graduate school at Emerson College, the focus was on the auteur—the singular vision of the writer-director. We were taught to protect our ideas fiercely, to execute them with precision, and to hold the reins tightly. There was an emphasis on authorship as ownership, on keeping your work purely yours.

But I’ve come to question that.

I’m not saying every piece of art has to be participatory or collaborative. Some works require solitude. But the idea that your singular voice must remain untouched, unshaken, and uninfluenced by others…depresses me. It feels like a form of arrogance that isolates more than it inspires.

Film, to me, is inherently collaborative. It demands it. The transformation that happens between participant and filmmaker during production, or between a rough cut and a fine cut during post production—those leaps and bounds you make—only happen with the right collaborators asking the right questions. A rough cut screening, for example, is only helpful if the people in the room understand your vision. If they want your film to be something it’s not, you can set those notes aside. But if they get what you’re trying to do and see where it’s falling short, they might offer ideas or questions that take you somewhere new.

That requires surrender. It requires listening. It requires trust.

And it’s not so different from life, really. Asking for help in art and asking for help in life are intertwined. Both require vulnerability. Both require letting go of the idea that you have to have all the answers or do it all yourself. And each time you open yourself to that, you gain something richer than what you could have created—or carried—alone.

It’s a reminder that art, like life, is never a solo act.

The other day, I texted a friend and asked for help with something small. Nothing earth-shattering. But I asked. And an hour later, he sent me photos of the work he’d done to help us.

It felt good.

I want to surrender more.

What about you? Do you struggle with asking for help? How do you let go of that need to do it all yourself?

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

P.S. Happy Birthday Mom - thanks for all that you do for me.

I'm always astounded at how long film credits are, beyond the mentions of all the actors. It takes so many people to make a movie. It's a little terrifying to imagine creating something and knowing that to pull it off you need that many folks, that many hands in your work, trying to carry out but not obfuscate your vision.

I admire the folks who can not only surrender, but who can bring in people that believe in their work as much as they do. Who can say: "Trust me with this." They almost build a community around their creativity. Because, in the end, we're creating with hope of it CONNECTING with others, right? Why shouldn't it connect with people who are being paid to do the work?

It's almost like working a job you love, where you aren't the star, but you believe in the vision or mission, versus doing it for the paycheck. I've been in both situations. And I've learned that if you want more of the first type of collaborators, you have to learn to not be either overly protective, scared, or an egomaniac.

Happy birthday to your mom!